Communications of the ACM

Preparing Computing Students For the Designer Role

Every two years, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics generates a ten years forward prediction on the labor marketplace. The latest statistics suggest a shift in how we think about computing careers.

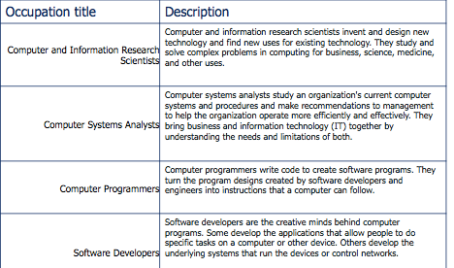

The BLS does not actually define the jobs that they predict. The definitions are developed by another department within the U.S. Department of Labor, which polls companies to figure out what their employees do. Here are some definitions relevant to us in computing (thanks to Lauren Csorny, an economist at BLS who prepared these).

Note the distinction between Programmers and Developers. Programmers write code that developers design. Software developers are the "creative minds behind computer programs."

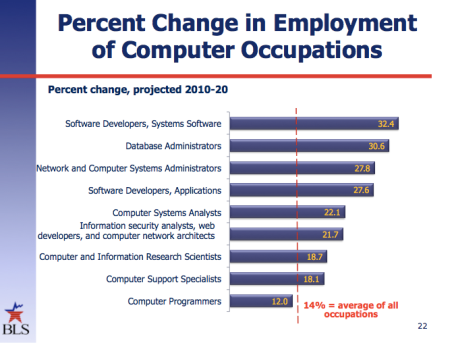

Here is the predicted percent change in these fields, 2010-2020.

What jobs do we want future computing graduates to do? Do we see them as filling the Computer Programmers slot, or the Software Developers slot? It's pretty clear that the growth in programming jobs in the US is pretty anemic, but the developer/designer jobs are going to grow enormously. If we want our graduates to be Software Developers, how should we get there? How should our curricula look different?

The most interesting implications are in what we teach about programming.

- Do designers need to be master programmers? Master programmers need years of experience to develop their expertise. Can we afford that much time, and still get to the design issues that we will want to emphasize? Janet Murray recently considered this question for games and media designers. She points out that the purpose of a designer learning programming is not to get them to build things for themselves — she says that that would dramatically limit the designers. Instead, she wants them to understand how code is created, what it can do, and how flexible it is. However, there are design issues that expert programmers don't get to: "But even expert programmers, especially the self-taught ones, can be ignorant of the key architectural principles that make for good design: information abstraction, modularity, and encapsulation."

- Do designers need to see multiple languages, rather than achieve expertise in one? Eugene Wallingford recently made that argument. We want designers to think about problems in different ways, creatively. "The greatest benefits come from learning different kinds of language. A new language that doesn’t stretch your mind won’t stretch your mind."

Clearly, it will be difficult for any software designer to land a job without programming skills. Andy Begel and Beth Simon did a study of new hires at Microsoft showing that they are hired for their programming skills, but do relatively little programming in their first year. Their job will involve more than programming. Our students' ability to be creative and think broadly is probably more important to success in the software designer/developer role than their mastery of a single language.

Comments

John Ebert

My undergraduate degree is in Architecture (building architecture, not computer architecture). This discussion about how to train software designers rather than programmers led me to think about how I was trained as an architect (as opposed to a builder). In every term in my architectural education, our most important class was a design studio. In these classes, we would design a building and produce drawings and models to present our design. What might be relevant to this discussion is that these were not toy problems - we were given real locations and requirements that were either real or could easily be real. Given the size and complexity of a building, there was no expectation that we would have time in a three month studio project to get into details, let alone actually build the thing. Evaluation was done by the professors in front of the whole class and they would bring up whatever issues seemed relevant. Sometimes they would get into details when it appeared that the design would be difficult or impossible to implement because certain real world constraints had been violated. But mostly the evaluation touched on implications and trade-offs among choices made - having many students solve the same problem provided lots of varied examples to consider - and listening to the discussion was valuable because it trained us in how to think and decide about design. I have the impression that most computer classes involve attempts to build actually working software and are contrained to the kinds of things that can be completed by working a few hours a day for a few months. Are there many classes that give students the opportunity to design a software system that might take a team of programmers a year or more to build?

Mark Guzdial

You raise a great point, John. I don't know of classes where students design but without a plan to implement, but such classes might exist somewhere. I'd be interested to hear how well they work.

Anonymous

One might consider the possibility that the bureau of labor statistics has no clue about the business of producing software. Where do they get their definitions - from economists making guesses?

Mark Guzdial

They get their numbers and job descriptions by surveying industry. See http://www.bls.gov/emp/nioem/empioan.htm for details on the surveys that they use.

Displaying all 4 comments