Communications of the ACM

Hour of Code: Observations from a Middle School Classroom

This afternoon, I volunteered at The Meadowbrook School, a private middle school outside of Boston, as part of the Hour of Code initiative. The organizers of the Hour of Code want to get every K-12 student in this country to try one hour of programming during this week, which is the annual CS Education Week. This article summarizes some observations from my day that are relevant to CS education.

Logistics

Last week, students in the middle school filled out an online survey about their prior programming experience and were assigned into one of three groups -- beginner, intermediate, or advanced. Today we gave each group a different activity to do for their hour in the computer lab:

- Beginner (no prior experience): Tynker exercises specially designed for Hour of Code, which is a graphical, blocks-based programming language similar to Scratch.

- Intermediate (a tiny bit of prior experience with Scratch, Lego Mindstorms, etc.): Codecademy JavaScript specially designed for Hour of Code, and then Python for those who finished early.

- Advanced (some prior programming experience): CodingBat Python or a custom Tic Tac Toe game, although several students ended up doing Codecademy Python instead since it provided step-by-step guidance.

These activities are mostly self-guided, and half a dozen volunteers such as myself walked around the room to help out as needed. Thus, we were not teaching in the traditional "lecture from the front of the room" sense.

Pair Programming

Margo Seltzer (one of the ringleaders of the volunteer crew) suggested that students pair up in front of a single computer, and that idea worked brilliantly! CS Education researchers have known this fact for years, but it's something that works so well that it's worth mentioning again.

Here were the main benefits that I noticed:

- Pairs could celebrate victories together, most notably yelling "YEAH!" and high-fiving after completing an exercise, or "OHHHHH!" after they successfully debugged some error. I loved hearing occasional bursts of excitement whenever students overcame a hurdle. If everyone were just in front of their own computer, then shared celebrations wouldn't exist.

- The observer (student who isn't programming) can often catch typos and syntax errors while their partner is typing. This is incredibly helpful since beginners often get stuck on typos and syntax errors.

- The observer can also look at what their neighboring pair is doing and either help them out, or ask them for help. I saw a few pairs helping out their neighbors, or at least competing with them to see who could finish the current exercise faster.

- Pairs kept each other on task, since there is a bit of social pressure to focus on the task at hand rather than just staring blankly at the screen or surfing the Web.

- Pairs seemed more willing to ask the volunteers for help, since it was like they were stuck on something together after trying to figure it out themselves first. A solo student might be more reluctant to admit to being stuck and either randomly poke around or disengage entirely and start surfing the Web.

- Pairs effectively cut the student-teacher-ratio in half. For instance, six volunteers roaming the room can easily give good attention to 12 pairs of students, but it's much harder to pay attention to 24 solitary students.

And some potential drawbacks:

- Pairing seemed great for "getting stuff done" -- i.e., plowing through the exercises quickly -- but I didn't see students pausing to reflect on or internalize what they had just learned. It was almost like they were playing a cooperative two-person game together, so there was some pressure to keep moving, nonstop. Again, pairing is great for "productivity," but perhaps some solo time for reflection would help students internalize the knowledge better.

- In rare cases, a dominant student would hog the keyboard/mouse and do most of the exercises while their partner just sat there watching passively. We tried to nudge students to take turns by passing the keyboard/mouse back and forth after each exercise. And usually most pairs did switch off in a natural way.

- Pairing makes the room really LOUD, so students who need quiet time to focus might be at a disadvantage.

- Introverts might not work as well in pairs (see below).

Voluntary pairing: Students chose their own partners, which seemed optimal since they were immediately comfortable with one another. I saw a lot of banter, lighthearted joking around, and candid back-and-forth like "gah! you missed a quote here! look!!!", which I think would've not existed had students been assigned a random partner.

Sometimes students (especially girls) wanted to stick together in a group of three close friends, so we let them. And there were some kids who didn't have a partner, so they programmed alone. I made sure to check up more on the few solo kids to make sure they weren't stuck; for the most part, they seemed like introverts who were fine making progress by themselves. (Has anyone researched the benefits of pair programming for introverts?)

Poking the screen: Another funny phenomenon was how students often poked the screen to indicate something to their partner. Sometimes they poked the screen so hard so that it would tilt. What if they had a touchscreen monitor that would register those pokes? Can we then create a better pair programming UI for education based on this commonly-observed behavior?

Web-Based Live Programming Environment

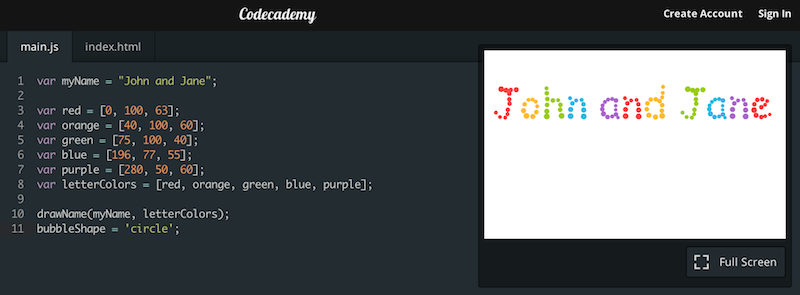

The Web-based live programming environment provided by Codecademy's JavaScript exercises combines an IDE with a live preview of graphical output that updates every time the student changes the code. In the exercise shown below, the drawName() function prints the contents of the myName string variable in color. Students had a blast typing in various nicknames and adjusting the colors and shapes.

This environment was really engaging because:

- Students can get started immediately by visiting a URL with no file downloads or installation. In contrast, some advanced students attempted to hack a Tic Tac Toe game, but they had to download a few Python files, locate them on their computer, find the Terminal app, learn to use a command-line interface, cd into the proper directory, set permissions, execute Python, and, most annoyingly of all, figure out which text editor to use, and how to use it ... all without the benefits of syntax highlighting.

- Syntax highlighting was very, very, very helpful. In contrast, CodingBat and the plain-text editors that the advanced students used didn't have syntax highlighting, so students made far more errors such as forgetting to put closing quotes on strings.

- Students got a real-time live preview of the effects of their code edits without needing to hit "Run," so they can immediately see the consequences of their tweaks. This interface felt so natural that students never even questioned it; they just assumed that all code was meant to work this way. I predict that those students will later question why they need a separate "Run" step when they program in, say, Python, in the future, or even worse, why they need two separate steps for "Compile" and "Run" in, say, C++ or Java.

The Codecademy Python inteface did not have graphics or live programming (i.e., there was a separate "Run" button), but it still had the benefits of no-installation and syntax highlighting. In general, it felt less polished than the JavaScript interface, with lots of tiny annoyances. (For instance, it would always print out an extra "None" at the end of execution, presumably because the implicit user-defined function returned None.)

Default error messages are useless (but ignored)

Anyone who has ever taught programming knows that system-generated error and warning messages are pretty much useless to beginners. In general, messages for run-time errors are a bit better than compile-time errors, since they are more specific. And syntax errors are the worst, due to vagaries in parser behavior. Warnings might seem helpful but are often cryptic and irrelevant to what beginners need to know. For example, one Codecademy JavaScript exercise starts with the following code shown to the student:

document.write( "yourName" );

The student is supposed to replace "yourName" with their own name. However, the IDE presumably hooks up to some Lint-like static analysis that generates warnings, because a warning pops up immediately on that line saying "document.write can be a form of eval." Wow, that was not only utterly useless, but it would confuse the heck out of me if that was my first exposure to JavaScript. I didn't even write any code yet and already see a warning!

I would recommend against directly piping errors and warnings from the underlying compiler/interpreter into an educational IDE. At the very least, the developers should filter out useless warnings like the one above and attempt to translate other ones into human-readable English.

Ironically, the only warning I noticed that would have been helpful to students -- use of an undefined variable in JavaScript -- was not provided. When students misspelled variable names, which often resulted in a use of an undefined variable, the Codecademy IDE just let the code execute and silently fail with no explanation whatsoever. Students were befuddled until I helped them track down their typos (which sometimes involved case sensitivity -- e.g., Name vs. name).

The silver lining here is that students quickly learn to ignore all warning and error messages. So I guess it's not so bad if you leave in useless messages; students just ignore them. This surprised me a bit, since when I observed adult beginners learning to program for the first time, they more often got hung up on trying to understand those cryptic messages. Perhaps kids are more "immune" to text-junk and don't have as much of a desire to make sense of everything they see on the screen. It would be interesting to run a study contrasting kids' and adults' perceptions of those sorts of computer-generated messages.

Good error messages for beginners are hard to create

In general, creating better error and warning messages for beginners is a very hard problem, since you need a robust model of common beginner misconceptions. For example, once I saw a student who needed to add two variables, a and b, and multiply by two. So what did he write?

2(a+b)

That's exactly how you would write it in math. But what error does Python give? Nope, not a syntax error. The code actually runs, and it tries to make a function call on the 2 literal, so it gives "TypeError: 'int' object is not callable" WTF?!? (Codecademy JavaScript says "Bad invocation", which sounds like a cool punk album name, but not a helpful error message.) Of course, the right answer is:

2*(a+b)

but how is a student who just came from math class supposed to know that? 2(a+b) looks perfectly correct in math syntax.

Problem-specific error messages are better but overly pedantic

The only error messages that students paid attention to were those that were custom-made for each problem. Students seemed to understand and heed those errors and quickly correct their code to eliminate them.

I don't know the exact interface that problem creators use to make these messages, but I'm assuming that there is some template based on regular expressions or run-time value traces. An AST-matching template language would be more powerful, but also harder to design and use; also, it would be tricky to handle code with syntax errors.

More nuance in those errors would be helpful, though. For instance, one problem asked a student to create a my_int variable and set it to 7. The correct answer is:

var my_int = 7;

The student wrote something like:

var my_int = 3;

since he liked the number 3 better than 7. However, the IDE yelled at him in big red letters that he was WRONG WRONG WRONG, and that he needed to set my_int equal to 7. He asked me, "Why do I need to set it to 7?" And he had a great point; 7 was just an arbitrary number with no significance whatsoever. His code was perfectly correct as-is; it wasn't like he had a syntax error or set my_int to a string. For all intents and purposes, he understood the concept of setting a variable to an integer literal but was punished by an error message just as severe as students who wrote garbage like:

var my_int hl2n3laf89uao3nl2n3sd9f34l

After all, both strings match "var my_int", so the system presumably fires off the error message that the problem creator designated for "if the student declared my_int but doesn't set it to 7, then print 'you need to set my_int equal to 7'".

How do we provide problem creators with more robust ways of specifying custom error messages?

Playful Diversions

Students seemed to learn the most when they diverted from the problem statements and just started playing around with the live coding environment. For instance, some problems printed out text in bright colors using variables such as:

var orange = [40, 100, 60];

Some curious students started playing around with those numbers to see how they would change the resulting colors. Other students wanted to create their own colors (pink was commonly requested) by copying and pasting an existing color variable and modifying it, like:

var pink = [40, 100, 60];

Students first assumed that those values were RGB (Red, Green, Blue), since those are primary colors. But they tried adjusting the numbers and saw that it wasn't behaving like RGB. It was, in fact, some other weird encoding scheme. One fellow volunteer walked by and yelled out, "cool, those values are RGB", trying to be helpful, but he was wrong. The students knew better since they had actually played around with the code!

Eventually the students figured out that the last number ranged from 0 to 100, with 0 being black and 100 being white. They couldn't figure out how to properly tune the first two numbers, though, and got frustrated. In fact, the numbers are in HSV format, which is not intuitive at all. But it was still better for students to play around and fail than to just receive the answer from an instructor (whose assumptions are probably incorrect). Again, the live coding environment helped a lot in facilitating such explorations.

Utterly Fearless

I was impressed by how utterly fearless the students were in hacking on their code -- tweaking, tuning, adding and deleting lines without hesitation. In contrast, the adult beginners whom I taught in a similar setting in August (shown below) were much more hesitant to play around with their code and dutifully followed directions as closely as possible.

There are several possible reasons for these differences:

- Kids, especially those who grew up with computers and electronic gadgets, are more accustomed to fiddling around with technology than adults.

- The students were using school-issued computers, while the adults were using their own personal laptops. Thus, the students probably didn't care if they accidentally crashed or screwed up the school computer, since their own data wasn't on it.

- The students were using a Web-based environment, while the adults were using software installed locally on their own computers. If the website froze, students just closed the browser and restarted. People intuitively understand that what goes on inside of a browser is "somewhere else" remote on a server on the Internet, not on their own computer. So they know that they won't screw up their computer, even if their browser crashes (barring extreme malware).

How can we inject this spirit of fearlessness into learners from more diverse demographics?

Gender (and Race)

Another salient observation was just how few girls (and other underrepresented minorities) were present in the advanced section. There were a fair number of girls and (non-Asian) minority students in the intermediate section; and although I didn't observe the beginner section, there must have been even more girls there, since the school is presumably gender balanced, and all students had to participate.

Okay, this fact alone isn't surprising, since there is a ton of research on how boys (especially white and Asian boys) in this country get far more positive and encouraging early childhood exposure to computers, so it's likely that they would have more prior programming experience.

But here's what was more interesting: I didn't think that many of the boys in the advanced section were all that advanced. One hypothesis is that the boys overrepresented their prior programming experiences (e.g., checking off a box that said they had programmed in language X even though they only briefly saw it once). Sure, there were a few outliers who were truly advanced, but for the most part, there weren't noticeable differences between the intermediate and advanced students.

I haven't done a formal study, but girls (and minority students) might have subconsciously self-selected themselves down to intermediate while the (mostly white and Asian) boys had no qualms about answering "yes" to some of the more advanced questions on the survey. (A semi-related anecdote: Some technical women I know wouldn't claim on their resume that they know programming language X unless they really knew it well, whereas men would just say that they know X even if they only used it briefly.) This phenomenon of minorities self-selecting downward is well-known to social scientists and education researchers, but it was still striking to see it firsthand.

Also, note that this is a top-ranked private school, so students here presumably rate much higher on self-efficacy than the majority of kids in this country who do not have access to such an excellent school. If girls and underrepresented minorities here might underrate their own abilities, I can't imagine how much worse this problem is in the rest of the country (much less, the world). We still have a long way to go before everyone who has the potential to excel in and love programming gets the opportunity to do so.

Random Tidbits

Here are some miscellaneous fun observations:

- Some students had never typed the '[' and ']' characters before and couldn't find them on the keyboard. They even asked, "What are these called?" That totally makes sense, since people don't usually type those characters when writing English.

- Some students thought that "bools" and "booleans" sounded funny.

- "floats? you mean like ice cream floats?"

- "I thought Python was just a big snake."

- Cool question: "Is this like how you write code on Tumblr" (referring to the markup language to style blog posts)

- A deeper set of questions: "So is this like math? How is this different than math? Would I need to know calculus later to do programming?"

Parting Thoughts

To me, the key metric of success was that most students were still obsessively programming when their hour was up and had to be ripped away from their computers. Very few students zoned out during the hour. Engagement was high all around, thanks in large part to the team of volunteers who helped students get unstuck at crucial moments.

Cynics might argue that students weren't truly "learning to code" -- they were just going through the motions, typing in keystrokes, following directions, and making colors appear on the screen. Well, of course nobody can expect students to deeply learn or retain anything from a single hour of programming! But the point of this event is just to give students a tiny taste of programming and hopefully motivate some of them to continue onward. And given those goals, I thought it was a rousing success!

No entries found