Communications of the ACM

Rising Enrollment Might Capsize Retention and Diversity Efforts

Georgia Institute of Technology professor Mark Guzdial

Computing educators have been working hard at figuring out how to make sure that students succeed in computer science classes -- with measurable success. The best paper award for the 2013 SIGCSE Symposium went to a paper that showed how a combination of pair programming, peer instruction, and curriculum change led to dramatic improvements in retention (see paper here). The chairs award for the 2013 ICER Conference went to a paper describing how Media Computation positively impacted retention in multiple institutions over a 10 year period (see paper here). The best paper award at ITICSE 2014 was a meta-analysis of papers that explored approaches to lower failure rates in CS undergraduate classes (see paper here).

How things have changed! Few CS departments in the United States are worried about retention right now. Instead, CS departments are looking for mechanisms to manage a rising tide of enrollment that threatens to undermine our efforts to increase diversity in computing education.

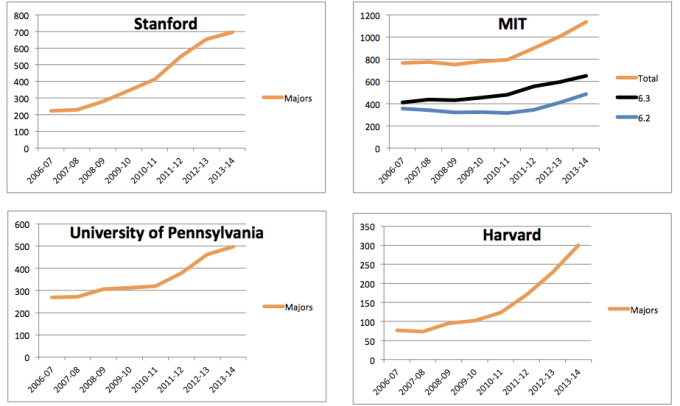

Enrollments in computer science are skyrocketing. Ed Lazowska and Eric Roberts sounded the alarm at the NCWIT summit last May, showing rising enrollments at several institutions (see article here and picture below). Indiana University has had their undergraduate computing and informatics undergraduate enrollment triple in the last seven years (see article). At Georgia Tech, our previous maximum number of undergraduates in computing was 1539 set in 2001. As of Fall 2014, we have 1665 undergraduates.

What do we do? One thing we might do is hire more faculty, and some schools are doing that. There were over 250 job ads for CS faculty in one recent month. I don't know if there are even enough CS PhD's looking for jobs to meet this kind of growth in demand for our courses.

Many schools are putting the brakes on enrollment. Georgia Tech is putting limits on transfers into the CS major and minor. The University of Massachusetts at Amherst is implementing caps. Berkeley now has a minimum GPA requirement to transfer into computer science.

We've been down this road before. Back in the 1980's when enrollment spiked, a variety of mechanisms were put into place to limit enrollment (see the story here). If there were too few seats available in our classes, we wanted to save those for the "best and brightest." From that perspective, a minimum GPA requirement made sense. From a diversity perspective, it didn't.

Even today, white and Asian males are far more likely to have access to AP Computer Science and other pre-college computing opportunities. Who's going to do better in the intro course -- the female student who is trying out programming for the first time, or the male student who has already programmed in Java? Our efforts to increase the diversity of our computing education are likely to be undermined by the efforts to manage the rise in enrollment. The students who get shut out by these kinds of limits and caps are most often those who are part of demographic groups that are already under-represented in computer science.

When you're being swamped by overwhelming numbers, retention isn't your first priority. When you start allocating seats, the students with prior experience look the strongest and the most deserving of the opportunity. Google is trying to help -- they've started a pilot program to offer grants to schools with innovative ideas to manage the enrollment boom without sacrificing diversity (see article here).

One reason for putting more computer science into schools is the need for computing workers (see an article from an Atlanta paper making this argument). What happens if these kids get engaged by activities like the Hour of Code, but then, can't get into undergraduate computer science classes? The linkage between computing in schools and a well-prepared workforce is broken. It's ironic that our efforts to diversify computing may be getting broken by too many kids becoming sold on the value of computing!

It is great news that students see the value of computing. Now, we have to figure out how to meet the demand -- without sacrificing our efforts to increase diversity.

Comments

Cassidy Alan

Thank God for the new paradigms for "education" that have come along with the Internet. If you want "diversity", you should be grateful for trends like the MOOC's, and the uprising of the "grassroots geeks" who are gathering in spontaneous meetups all over the world.

There's one for academics in computing university-land: study the technical and computing meetups. I have gone to several for many different computing languages and methods, including some with cross-functional themes. Veterans in software that love sharing their experience with newcomers and talking shop and sharing pointers among themselves.

The combination of the Internet and Open source has opened vast new horizons that are toppling traditional paradigms of education, computing, science, and everything else and the industries that associate with those respective areas. Computers are the hardware for all this change, and networking is the communications systems, and it's all just beginning.

The biggest danger to diversity, and to advancing the cause of computing science and education and practice, and to science, is in all these "social engineering" efforts, which seem to acquire an institutionalized life of their own, complete with humans who depend on those institutions for their purpose and livelihood. So they seek new windmills to slay, even though the new windmills are just piles of legacy junk that are already dead. Better to declare victory and move on to the next dragon to slay.

The worst barriers to racial diversity, for example, were Jim Crow laws and their legacy. Culture plays a part, but culture by royal government decrees and politicizing your diversity ideas into mandates result in distortions you won't want.

Mark Guzdial

What's striking is how non-diverse these new Internet education technologies have been. CS MOOCs are even more white and male than face-to-face CS classes (http://herminiaibarra.com/hiring-and-big-data-those-who-could-be-left-behind/). On-line learning opportunities like Scratch are more even more male than high school CS classes (https://computinged.wordpress.com/2014/11/21/programming-with-pseudocode-keeping-student-interest-the-need-for-school-and-international-curricula-trip-report-on-wipsce-2014/), which is really hard to believe (see our nationwide analysis of AP CS data from SIGCSE 2014 http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2538862.2538918&coll=DL&dl=ACM). The Maker movement is "mostly rich, white guys" to quote Leah Buechley's recent talk (https://computinged.wordpress.com/2014/12/17/makers-are-mostly-rich-white-guys-broadening-participation-in-computing-requires-formal-education/).

The reality is that our best chance to improve diversity is through school. This is an old debate. Seymour Papert and Paulo Freire publicly had this debate in 1980 (see a brief description, with links to video and transcript at http://trice25.edublogs.org/2011/07/17/back-to-the-future-of-education-papert-vs-freire/). Seymour Papert wanted to do away with school using computing technology. Paulo Freire admitted the flaws of school, but recognized it as the most important tool we have for providing education to the poor and under-privileged.

Displaying all 2 comments