Communications of the ACM

The Model Maker of Leonardo da Vinci, Blaise Pascal, and Charles Babbage

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) produced a wealth of technical drawings (Codex Atlanticus, Codex Madrid). He already knew, for example, the gear train, the rack and pinion, the cam, the Nuremberg scissors, the sector, and the odometer cart, and is said to have designed a calculator. But the interpretation of his sketches is not always easy.

The Italian engineer Roberto A. Guatelli (1904–1993), who was world-famous at that time but is now forgotten, not only produced countless models of Leonardo da Vinci, but also built replicas of numerous calculators; e.g., the adding and subtracting machine of Blaise Pascal, the four-function calculating machine of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the difference engine of Charles Babbage, the census machine of Herman Hollerith — and also, as I have just learned, the Millionaire direct multiplier from Zurich (cf. Fig. 1–2). The outstanding replicas are often very similar to the original devices. In 1968, Guatelli rebuilt Leonardo da Vinci's "calculating machine." However, it is controversial whether this is actually a calculator.

Open questions

To my knowledge, there is no list of the models that Roberto Guatelli manufactured based on the drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. It is also unclear which and how many calculators he built for IBM New York and other clients and how many are preserved.

It is not known where the original Millionaire machine (maker number 2380), which Guatelli rebuilt, is located. It is missing in the Australian "Register of Millionaire Calculators" by John Wolff. The Millionaire in the collection of the IBM Corporate Archives in Poughkeepsie, NY, has the number 403. The four copies at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, which collaborated with IBM, have different serial numbers.

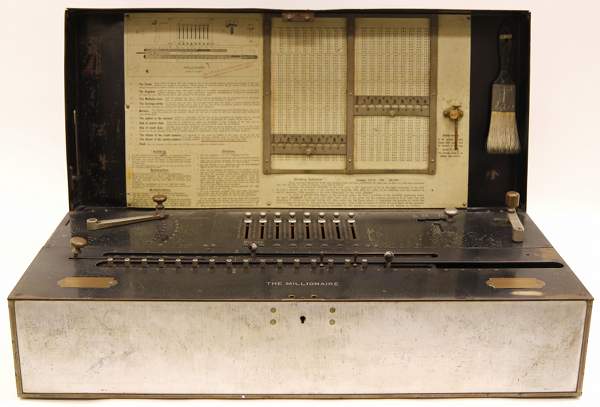

Fig. 1: Millionaire direct multiplication machine 1 (Guatelli replica). Figures are entered with the setting levers.

The values are transferred to the accumulator with the crank (top right).

At top left, the multiplication lever, which accelerates multiplications.

Credit: Heidi Wiren Bartlett, designer, University Libraries, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburg, PA

At present, the following Guatelli replicas of calculating machines can be detected:

Known Replicas of Calculating Machines

Museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnologia "Leonardo da Vinci," Milan, Italy

- Pascaline

Replica. Several different original devices (c. 1643) have been preserved (e.g. Clermont-Ferrand, Paris, Dresden, New York).

According to the "Catalogo regionale Lombardia beni culturali," Guatelli also rebuilt the calculating machine of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1694). The only surviving machine is at the Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz Library in Hannover.

Computer History Museum, Mountain View, CA

- Pascaline

Replica (1981). Several different original devices (1645) have been preserved (e.g., Clermont-Ferrand, Paris, Dresden, New York). - Difference engine no. 1 (trial piece) by Charles Babbage

Reproduction (1972) of the original engine from 1833, which is located at the Science Museum in London. - Census machine (tabulator and sorter) of Herman Hollerith

- Electric tabulating system by Herman Hollerith

Canada Science and Technology Museum, Ottawa

- Pascaline

Replica (c. 1978). Several different originals (c. 1643) have been preserved (e.g., Clermont-Ferrand, Paris, Dresden, New York). - Difference engine no. 1 (trial piece) by Charles Babbage

Reproduction (1972) of the original engine from 1833, which is located at the Science Museum in London.

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Traub-McCorduck Collection)

- Millionaire

The first copy of the Millionaire of H.W. Egli Ltd., Zurich, was manufactured in 1893. The original machine with serial number 2380 was produced around 1916.

IBM Corporate Archives in Poughkeepsie, NY

In the IBM archives there are numerous replicas, which possibly originate (in part) from Guatelli: An analytical engine by Charles Babbage, Pascaline, calculating machines by Leibniz, Leupold/Braun/Vayringe, Morland, a difference engine by Charles Babbage (trial piece), a difference machine 2 by Edvard and Pehr Scheutz. Unfortunately, no information is available.

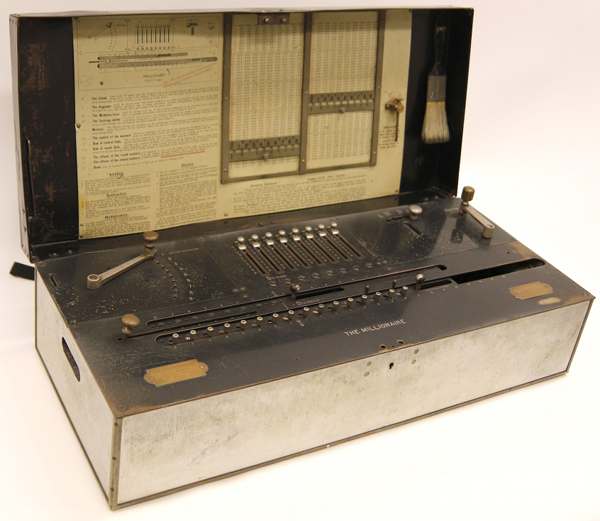

Fig. 2: Millionaire direct multiplication machine 2 (Guatelli replica).

Above is the setting mechanism with the setting levers,

in the middle and below are the revolution counter and the result register.

The very heavy machine is able to perform all four basic arithmetic operations.

Credit: Heidi Wiren Bartlett, designer, University Libraries, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA

Excerpts from Two American Publications

Francis C. Moon of Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, writes: "One of the most famous sets of Leonardo models was commissioned by the Italian dictator Mussolini for an exhibition in 1939 in Milan as a part of an effort to build national pride in Italian history. The 200 models were built by an Italian engineer, Roberto A. Guatelli at a cost of $250,000 (Time Magazine, May 29, 1939, p. 39). These models went on tour and ended up in Japan where they were destroyed during World War II. After the war, Guatelli was commissioned to make a smaller set of 66 models for an exhibition at IBM headquarters in New York City in 1951. With the recent demise of the IBM museum in New York, these models have been dispersed and are on occasional tour in various exhibitions" (see Francis C. Moon: The Machines of Leonardo da Vinci and Franz Reuleaux, Springer, Dordrecht 2007, page 201).

David Pantalony of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, Ottawa, tries to explore the provenance of models: "Since the 1930s, IBM's founder, Thomas Watson Sr. had been collecting antiques and books related to the history of calculating and computing. They were first exhibited at the 1939 World's Fair […]. In 1951, Watson channeled this interest toward Leonardo da Vinci and a travelling exhibition of his machines. A few years earlier, Watson had seen an exhibit of replicas made by the Italian artisan and scholar Roberto Guatelli; he subsequently bought the collection and hired Guatelli. Thus began a long relationship between Guatelli and IBM.

"Roberto Guatelli (1904–1993), a science and engineering graduate from the University of Milan, developed his reputation by building and exhibiting interpretations based on the work of Leonardo da Vinci. In 1939, fitting the nationalist context of the time, the Italian government sponsored a major exhibition of Leonard da Vinci models at the Palazzo dell'arte Milan. […]. The Italian ministry of culture then sponsored a travelling version for the United States. In 1940 Guatelli, emerging as one of the leading model makers, travelled to New York for an exhibition at the Museum of Science and Industry in the Rockefeller Center […]. Guatelli and his models were a travelling sensation in post-World War II America." (see David Pantalony: Collectors, Displays and Replicas in Context: What We Can Learn from Provenance Research in Science Museums, in: Jed Buchwald; Larry Stewart (eds.): The Romance of Science: Essays in Honour of Trevor H. Levere, Springer International Publishing AG, Cham 2017, pages 271–272).

References

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston 2018, 2 volumes, 1600 pages (Milestones in analog and digital computing, English translation forthcoming)

Buchwald, Jed; Stewart, Larry (eds): The Romance of Science: Essays in Honour of Trevor H. Levere, Springer International Publishing AG, Cham 2017, ix, 310 pages

Kaplan, Erez: The controversial replica of Leonardo da Vinci's adding machine, in: IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, volume 19, 1997, no. 2, pages 62–63

Moon, Francis C.: The Machines of Leonardo da Vinci and Franz Reuleaux, Springer, Dordrecht 2007, xxxiii, 417 pages

Pantalony, David: Collectors, Displays and Replicas in Context: What We can Learn from Provenance Research in Science Museums, in: Jed Buchwald; Larry Stewart (eds.): The Romance of Science: Essays in Honour of Trevor H. Levere, Springer International Publishing AG, Cham 2017, pages 268–274

Strickland, Jim: Who was that guy? Roberto Guatelli, in: Computer History Museum, Volunteer Information Exchange, volume 2, February 15, 2012, no, 3.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Andrew Rosenbloom, senior editor of Communications of the ACM (New York), who drew my attention to the Traub-McCorduck Collection at Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA. I am very grateful to Mary Catharine Johnsen, Special Collections Librarian, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries; she told me about the Millionaire replica and provided the beautiful photos.

Herbert Bruderer is a retired lecturer in didactics of computer science at ETH Zürich. More recently, he has been an historian of technology. [email protected], [email protected]

No entries found