Communications of the ACM

AI Began in 1912

A workshop held in 1956 at Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, is usually considered the beginning of artificial intelligence. Participants included John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky. Alan Turing and Konrad Zuse, who already dealt with this topic in the 1940s, are also mentioned as the founders of this discipline.

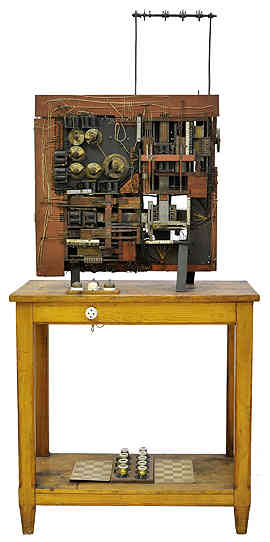

For decades, machine chess was considered the highlight of artificial intelligence. It was not until 1997 that IBM's Deep Blue program was able to beat then-world chess champion Garry Kasparov. Today, programs such as AlphaGo zero and AlphaZero from Deepmind (Google) master much more difficult games using artificial neural networks. If one takes chess as a yardstick for artificial intelligence, however, this branch of research begins much earlier, at the latest in 1912 with the chess automaton of the Spaniard Leonardo Torres Quevedo (cf. Fig. 1). In the chess-playing Turk (1769) of Wolfgang von Kempelen, a human player was hidden.

Torres Quevedo showed his electromechanical chess machine (El ajedrecista, chess player), developed from 1912, in the machine laboratory of the Sorbonne University in Paris in 1914. The endgame machine was able to checkmate the king of a human opponent with a rook and king.

Figure 1: The first chess automaton of Torres Quevedo.

This electromechanical endgame machine (1912) is considered the first chess machine in the world.

Credit: Museo Leonardo Torres Quevedo, Madrid

In 1951, Norbert Wiener played against the second model (1922) at the Paris computer conference, see https://cacm.acm.org/blogs/blog-cacm/222486-the-birthplace-of-artificial-intelligence/fulltext. The Austrian computer scientist Heinz Zemanek, who played against this chess machine at the Brussels World Fair in 1958, described it as a historical automaton that was far ahead of its time. According to Zemanek, Torres Quevedo designed a very clever six-part algorithm for the end game, which was implemented using levers, gears, and relays.

References

- Ashby, William Ross: Can a mechanical chess-player outplay its designer?, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, volume 3, 1952, issue 9, pages 44–57

- Ashby, William Ross: Mechanical chess player, Claus Pias (ed.): Cybernetics. The Macy conférences 1946–1953, Diaphanes, Zurich, Berlin 2016, pages 651–653

- Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, 2nd edition 2018, 2 volumes, 1600 pages

- Bruderer, Herbert: Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, 3rd edition 2020, 2 volumes, 2000 pages

- Ensmenger, Nathan: Is chess the drosophila of artificial intelligence? A social history of an algorithm, Social Studies of Science, volume 42, 2012, issue 1, pages 5–30

- Levy, David: Alan Turing on computer chess, S. Barry Cooper; Jan van Leeuwen (eds.): Alan Turing, His Work and Impact, Elsevier, Amsterdam. 2013, pages 644–650

- Marsland, T. Anthony; Schaeffer, Jonathan (eds.): Computers, chess, and cognition, Springer-Verlag, New York. 1990

- Shannon, Claude Elwood: A chess-playing machine, Scientific American, volume 182, February 1950, pages 48–51

- Standage, Tom: The mechanical Turk. The true story of the chess-playing machine that fooled the world, Allen Lane The Penguin press, London, New York 2002, xiv, 274 pages

- Torres-Quevedo, Gonzales: Présentation des appareils de Leonardo Torres-Quevedo, in: Joseph Pérès (ed.): Les machines à calculer et la pensée humaine, Paris, 8–13 January 1951, Colloques internationaux du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, CNRS, Paris 1953, pages 383–406

- Vigneron, Henri: Les automates, in: La nature, volume 42, 1914, issue 13, pages 56–61 (Torres Quevedo)

- von Windisch, Carl Gottlieb: Inanimate reason; or a circumstantial account of that astonishing piece of mechanism, M. de Kempelen's chess-player; now exhibiting at No. 8, Savile-Row, Burlington Gardens; illustrated with three copper-plates, exhibiting this celebrated automaton in different points of view, S. Bladon, No. 13, Pater-Noster-Row, London 1784, 58 pages

- Zemanek, Heinz: Spanische Automaten, Elektronische Rechenanlagen, volume 8, 1966, issue 6, pages 271–272.

Herbert Bruderer is a retired lecturer in didactics of computer science at ETH Zürich. More recently, he has been an historian of technology. [email protected], herbert.bruderer@bluewin.

No entries found