Communications of the ACM

Lessons from PL/I: A Most Ambitious Programming Language

One might argue that language creation might be accelerating today, but it's not a new problem. In my BLOG@CACM post "Why are there so many programming languages?" I described how variants of programming languages go back to the dawn of computer programming. In that post I also cited one of my favorite stories: PL/I. PL/I stands for Programming Language 1, and its aim was to be the Highlander of programming languages: there would be no need for 2, 3, or 4 if everything went to plan. While it is clear today that goal was never reached, what might not be evident is that what PL/I was trying to achieve was a pretty reasonable idea, or at least not entirely crazy. What also wasn't evident at the time was how enormously difficult that reasonable idea turned out to be. We can all learn something from this story.

The General Idea

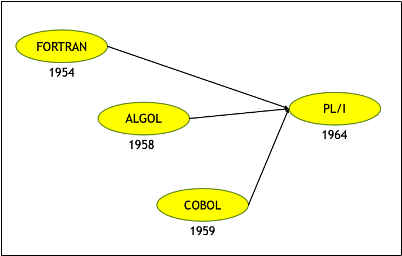

PL/I was designed by IBM with the goal of bringing together the power of 3 different programming languages: FORTRAN (1954), ALGOL (1958), and COBOL (1959).

- FORTRAN – The scientific programming language

- COBOL – The business programming language

- ALGOL – Primarily a research language, but with innovative paradigms and features

On paper, this makes a lot of sense. Computer programming can be difficult, and why should there be multiple programming languages? And because computer programming of the era required a lot of punched cards, having One Good Programming Language would have on paper (or cardboard) benefits to simplify the process of development as well. Work on the PL/I specification started in 1964, and work on the first compiler in 1966.

This was playing out within a decade of the creation of the first mainstream high-level programming language (FORTRAN), and even by that point there were arguably already "too many" languages. PL/I was a solution to at least a part of that problem.

The Hard Part

In the minds of PL/I's designers the plan looked something like this…

Credit: Doug Meil

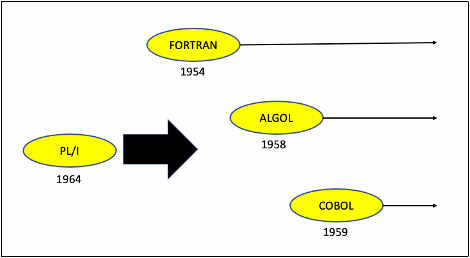

But PL/I wasn't just a development effort, it was also in effect a system conversion. There was an explicit goal for developers to start using PL/I, but were also implicit goals for developers not just to only stop using FORTRAN, COBOL, and ALGOL directly, as well as to convert their existing solutions and codebases to PL/I. As if that wasn't hard enough, compounding the problem was that FORTRAN, COBOL, and ALGOL were all evolving in real time. As I described in my BLOG@CACM post "The Art of Speedy Systems Conversions," a system conversion is one of the most difficult things to do in software engineering. The existing system typically has massive head start, and the replacing system needs to start up development, accelerate, reach feature parity, and then both systems need to be stable long enough to make the switch.

Credit: Doug Meil

Refer to the 1994 action movie Speed as to why this set of activities can be a challenge. PL/I was trying to do this with not just one mobile target, but three.

The FORTRAN Hard Part

All programming language evolve over time, and this was certainly true of FORTRAN. Some of the development milestones from early FORTAN were:

- FORTRAN language specification created by IBM (1954).

- FORTRAN 1 (1957)—First FORTRAN compiler available.

- FORTRAN 2 (1958)—This version had incremental language feature additions, including allowing user-written subroutines.

- FORTRAN 3 (1958)—This version was apparently never released as a product.

- FORTRAN 4—Development started in 1961 and was initially released in 1962 – but had subsequent development through 1968.

- FORTRAN 66 (1966)—This version became the first industry standard version of FORTRAN.

- FORTRAN 77 (1977)—More language feature additions, particularly trying to address shortcomings of FORTRAN 66.

Note that FORTRAN 66—a significant milestone in FORTRAN's history—happened multiple years after PL/I development had started.

The ALGOL Hard Part

ALGOL was highly influential programming language, and although primarily used in research and academic settings it still had an evolutionary arc:

- ALGOL 58 (1958)–First version of ALGOL. Included code blocks, an innovation in programming language design.

- ALGOL 60—While not commercially successful, widely used in research and hugely influential in language design. One of the first languages to implement function definitions that could also be called recursively, among other language features.

- ALGOL 68—A language specification intended as an improvement on ALGOL 60 that seemed to make just about everyone involved in the effort unhappy.

The COBOL Hard Part

COBOL Origins

When people think of COBOL now, they typically think of staid mainframe banking, finance, and insurance solutions, but COBOL's origins have a dash of drama. For starters, COBOL was designed in 1959 by CODASYL—an industry committee—which was part of a U.S. Defense Department effort to create a common data processing language that could run across the various computers it was operating. That simple-sounding requirement was anything but at the time, and is another example of the desire for One Good Programming Language, as well as compilers that could run on all those various computers. Second, there were already two prominent "business" programming languages in existence before COBOL: FLOW-MATIC and COMTRAN:

- FLOW-MATIC—Created by Grace Hopper when she was at Remington Rand from 1955 to 1958. FLOW-MATIC was English-based.

- COMTRAN—COMTRAN was created by IBM in 1957 and was intended to be "FORTRAN, for business."

There are varying opinions on how much each language influenced COBOL, though COBOL did wind up becoming quite verbose. Despite rumors to the contrary, Grace Hopper was not on the committee that designed the language.

Early COBOL

Some of the development milestones from early COBOL were:

- COBOL 60 (1960)—The first version of COBOL

- COBOL 61—Minor improvements to the language.

- COBOL 61 Extended—This version of COBOL appeared in 1963, including the sort and report writer facilities.

- COBOL 65—This version of COBOL brought further clarifications to the specification and introduced facilities for mass storage files and tables.

- COBOL 68—This version of COBOL eventually became an ISO standard in 1972.

- COBOL 74 —More changes to the language, including sub-programs.

IBM announced it would cease development of COMTRAN in 1962, in preference of COBOL.

The Historical Verdict

When compared to the thousands of other programming languages that have been created in the past 60+ years, PL/I was a success. PL/I reportedly was used in the development of the Multics operating system and the S/360 version of Sabre airline reservation system, among others. PL/I was taught at the college-level. PL/I has been around for decades. Most programming languages would be envious to do half as well.

But PL/I didn't achieve its strategic goal of consolidating scientific and business computing with the best new programming paradigms that research could provide, and it wasn't for a lack of trying. That goal, although well-intentioned, became impossible as both FORTRAN and COBOL kept accelerating. In terms of adoption, COBOL became the most widely used programming language in the world by 1970, and ripping out an existing COBOL system and replacing it with PL/I was going to be a hard sell to customers. The same could surely be said of existing FORTRAN systems. COBOL and FORTRAN also kept accelerating in terms of language definition during the 1960s, making PL/I's feature parity with them not just a challenge, but also ambiguous as it took both COBOL and FORTRAN years to stabilize their own respective standards.

The programming language landscape continued to evolve as well. By the end of the 1960s, Simula had branched from ALGOL and introduced object-oriented programming concepts, generating a new programming paradigm and host of new languages implementing those concepts, and C emerged as the dominant systems programming language the following decade. There were even more high-level programming languages than ever.

Lessons For The Rest Of Us

A system conversion is one of the hardest things to do in software engineering, and programming languages are one of the hardest sub-cases as its users are other developers. Exclaiming "we should rebuild it!" is a siren call that is tough to resist, though, as developers love the sight of a clean sheet of paper combined with a Big New Idea. It's not wrong to think big, just don't forget to plan for the conversion of the incumbent system: for every blank sheet of paper used to design the new thing, pull out at least one more for the migration. Keep that ratio in mind when considering timelines and the project budget as well, depending on just how deep the prior system is entrenched.

References

- Relevant BLOG@CACM Posts

- Film

- Highlander (film)

- "There can be only one" works in action movies, harder in programming.

- Speed (film)

- Helpful guidance on managing a complex rescue/systems migration.

- Highlander (film)

Doug Meil is a software architect in healthcare data management and analytics. He also founded the Cleveland Big Data Meetup in 2010. More of his BLOG@CACM posts can be found at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/publications-doug-meil

Comments

Paul McJones

I think you captured why PL/I failed to replace the other languages even though it was widely used in the IBM world and still exists today (but not for Windows?).

Displaying 1 comment