Communications of the ACM

Why Peer Review Matters

At the most recent Snowbird conference, where all the chairs of computer science departments in the U.S. meet every two years, there was a plenary session during which the panelists and audience discussed the peer review processes in computing research, especially as they pertain to a related debate on conferences versus journals. It’s good to go back to first principles to see why peer review matters, to inform how we then would think about process.

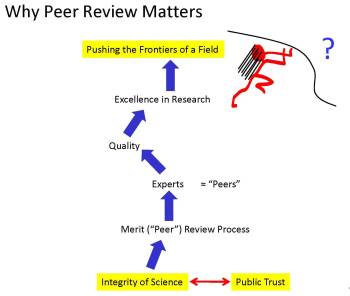

In research we are interested in discovering new knowledge. With new knowledge we push the frontiers of the field. It is through excellence in research that we advance our field, keeping it vibrant, exciting, and relevant. How is excellence determined? We rely on experts to distinguish new results from previously known, correct results from incorrect, relevant problems from irrelevant, significant results from insignificant, interesting results from dull, the proper use of scientific methods from being sloppy, and so on. We call these experts our peers. Their/our judgment assesses the quality and value of the research we produce. It is important for advancing our field to ensure we do high-quality work. That’s why peer review matters.

In science, peer review matters not just for scientific truth, but, in the broader context, for society’s perception of science. Peer review matters for the integrity of science. Scientific integrity is the basis for public trust in us, in our results, in science. Most people don’t understand the technical details of a scientific result, let alone how it was obtained, what assumptions were made, in what contexts the result is applicable, or what practical implications it has. When they read in the news that “Scientists state X,” there is an immediate trust that “X” is true. They know that science uses peer review to vet results before they are published. They trust this process to work. It is important for us, as scientists, not to lose the public trust in science. That’s why peer review matters.

“Public” includes policymakers. Most government executives and congressional members are not scientists. They do not understand science, so they need to rely on the judgment of experts to determine scientific truth and how to interpret scientific results. We want policymakers in the administration and Congress to base policy decisions on facts, on evidence, and on data. So it is important for policymakers that, to the best of our ability, we, as scientists, publish results that are correct. That’s why peer review matters.

Jeannette M. Wing Jeannette M. Wing |

Comments

Christian Timmerer

Thanks for this article. I also believe that the process shall be revisited and social networks shall be exploited for that purpose. I've blogged about that some time ago: http://multimediacommunication.blogspot.com/2010/02/science-20.html

Daniel Lemire

It is important for us, as scientists, not to lose the public trust in science. Thats why peer review matters.

I think we must continue to educate our students and the public about truth. Even if a research paper is published in the most respectable venue possible, it could still be wrong. Conventional peer review is essentially an insider game: it does nothing against systematic biases. (If everyone in a field is convinced that A must be good... then papers saying that A must be good will not get in trouble... even if the statement is false.)

Doubt must be cultivated always. As scientists we must doubt ourselves, our peers. We must train people around us to always keep some doubt.

In Physics, almost everyone posts his papers on arXiv. It is not peer review in the conventional sense. Yet, our trust in Physics has not gone down. In fact, Perelman proved the Poincar conjecture and posted his solution on arXiv, bypassing conventional peer review entirely. Yet, his work was peer reviewed, and very carefully.

So, I see no evidence that conventional peer review is necessary. I should stress that it is a relatively recent invention. It became a convention sometimes after WWII. Thus, Einstein, Turing and their contemporaries did fine without it.

its a whole other question of what the best process is for carrying out peer review

I think we urgently must distinguish between conventional peer review and peer review as a whole. Peer review includes reviews from practitioners and even outsiders (people from other fields). These people are typically omitted the conventional peer review.

We must urgently acknowledge that our traditional peer review is an honor-based system. When people try to game the system, they may get away with it. Thus, it is not the gold standard we make it out to be.

Moreover, conventional peer review puts high value in getting papers published. It is the very source of the paper counting routine we go through. If it was as easy to publish a research paper as it is to publish a blog post, nobody would be counting research papers. Thus, we must realize that conventional peer review has also some unintended consequences.

Yes, we need to filter research papers. But the Web, open source software and Wikipedia have shown us that filtering after publication, rather than before can work too. And filtering is not so hard. For example, maybe I trust Jeannette M. Wing. If so, I might be willing to trust what she writes... whether it was formally peer reviewed or not. Similarly, I might trust (and want to read) the research papers that Jeannette M. Wing has liked.

Filtering after publication is clearly the future. It is more demanding from an IT point of view. It could not work in a paper-based culture. But there is no reason why it can't work in the near future. And indeed, the Perelman example shows that it already works.

Further reading:

http://www.daniel-lemire.com/blog/archives/2010/09/06/how-reliable-is-science/

Eduardo Valle

Interesting post.

I particularly agree with you on the idea that peer review is invaluable, but it does not have to follow the conventional models of the past. Maybe a new, collective web of "trust", "authority", "reliability", and even "wisdom" can, with the correct tools, be harnessed from the apparent chaos of social networks.

The issues of scientific appraisal x publication venue have often been amalgamated. In the past, there was an implicit agreement that, in the sequence Technical Report => Conference Paper => Journal Paper => Book Chapter, an idea would pass through progressively stricter tests of "value" (in the dimensions of relevance, novelty, technical correctness, etc.) This model, however, no longer works.

A new system of "value" and confidence is already emerging, but what does it look like? Do we like the shape it is taking?

I have a feeling that times ahead will be challenging, but very exciting, to be a scientist.

Anonymous

Policymakers and scientists themselves have shown, including peer review processes, that neither of them respects truth as much as most of the public thinks. The day of that amorphous idea that "science" and scientists are free of human foibles is dead. Climategate shows that public policy has also helped tilt "science", government decisions on research dollars warps the scene. Joao Magueijo's battle with peer reviewers is another example.

Thank God Fleischman and Pons simply announced their experience without waiting, and in spite of opposition from Establishment Science labs got praise from Arthur Clarke and others are now starting to find promising potential from a new clean energy technology with massive potential.

N vs NP and Mr. Lamire's example of the Poincare conjecture show that transparent, public peer review in the sunshine of the Web can make new knowledge available much quicker than traditional paper, and with better quality than two or three anonymous reviewers who have their own fish to fry.

Mark Wallace

Professor Wing writes:

"Most people dont understand the technical details of a scientific result, let alone how it was obtained, what assumptions were made, in what contexts the result is applicable, or what practical implications it has."

That is a problem which we, as a society, cannot tolerate. Science cannot be reserved for a high priesthood, whose mysteries are forever hidden from the unwashed masses, and whose findings are cast down as divine revelations, never to be understood, let alone questioned.

While I may never know as much about her subject area as Professor Wing, I believe that I, as an educated layman, am competent to judge her use (or misuse) of the scientific method.

And, against Professor Wing's evaluation, I submit one from Albert Einstein: "If you can't explain it to a six year old, you don't understand it yourself."

"When they read in the news that Scientists state X, there is an immediate trust that X is true.""

Not any more.

"They know that science uses peer review to vet results before they are published. They trust this process to work."

A lot of us don't. There is too much cronyism, where "one hand washes the other."

"It is important for us, as scientists, not to lose the public trust in science."

Too late.

Professor Wing writes of a science that no longer exists, and, perhaps, never existed. In her mind, scientists are wholly disinterested seekers of truth, with not a single corrupt motive in their bones.

The truth is that scientists can be motivated, including in their professional work, by ego, greed, jealousy, vanity, envy, rivalry, petty animosities, and a host of other unfavorable traits, exactly like us "lesser mortals." The fact that their subject matter may be arcane makes it even more tempting to (as Daniel Lemire has already written) "game the system."

None of these observations originated with ClimateGate (but they were certainly reinforced by it). For excellent references on this general subject (the corruption of modern intellectual processes), please see:

"The Economic Laws of Scientific Research," by Terence Kealey (1997), and "Disciplined Minds," by Jeff Schmidt (2000).

So, I hope Professor Wing will forgive me if I sit here with my mere bachelor's degree in liberal arts, but yet still decline her invitation to, whenever she presents me with a peer-reviewed research finding, "just take her word for it."

To the extent the underlying problem can be fixed, it will require a revolutionary improvement in the way STEM subjects are taught to high school students.

Anonymous

Peer review would really be nice if reviers wuold really do their job. I got so many reviews where I was sure that some of them never read the paper (like blaming for not defining terms where the definition is clearly seen in the paper and so on). But well - why do a proper review, your name is on the committee page - so you got the honour and you can just throw a coind whether or not you accept/reject a paper.

Peter Johnston

Imagine if a team just came out with a new car. But all the magazines which reviewed it were staffed with people who had been part of the design team for the previous model.

How good would those reviews be?

And if that car's success relied on good comments from those people, how successful do you think it would be?

Secondly I assume you are aware of the idea of an economic moat.

Where people who have created a successful business model, then raise the barriers to entry to stop new people becoming competitors.

Well that happens in publishing too.

Imagine I'm Professor X, making 7 figures a year on the lecture circuit, talking about my theory.

Then someone comes up with a new theory.

Do I

a. Endorse it. After all, it is advancing my field of study.

b. Deny it - my theory is right.

c. Undermine it - damn it with faint praise, sow Fear, uncertainty and doubt.

d. Stall publication by peer reviewing it and asking for a host of revisions to accommodate my theory.

Human nature predicts Peer Review is a corrupt old boys network, not a benefit to science or even pseudo-science. And it is only the lack of peer review which allows me to write this. You will publish it, won't you? ;0)

PS: I was put through the most horrendous joining procedure simply to comment here. If you want to discourage open-ness and comments this couldn't have been better designed.

Displaying all 7 comments