Communications of the ACM

UIST 2010: Ending Keynote

I finally decided to take the train from my hotel to the conference site on the last day of UIST. For the past couple of days, I’ve been trying to avoid taking the train because of a lot of reasons: first, I had a little bit of trouble locating the train stations; second, I was confused by the "local" and "express" tracks and the weekend constructions in the transportation system; and third, I’m so accustomed to walking after three years of life in Boston. I still had trouble with the trains this time, but I’m getting better at it.

In the past two days, we were trying to hook up wireless internet for conference attendants, but perhaps Verizon underestimated the number of connections initiated by three hundred computer scientists, and we ended up having technically no internet access at the venue. But thanks to the absence of WiFi, I observed an increased amount of interpersonal communication in this year’s UIST than at other conferences I attended: people started asking each other for directions, as if we were back in the 1980s. Besides New Yorkers, those with an iPhone also acted as a major source of information: the fact that they had internet access and could find directions for others became a reason for face-to-face communication in such a situation. A friend of mine told me years ago that he would probably be “happier if computers did not exist”. This is probably not true in a lot of situations, but I came to think now that it makes sense in others.

This is somewhat related to the ending keynote given by Jaron Lanier. Any computer scientist has probably heard of his name multiple times, which has appeared on movies and TVs, as well as on the TIME 100 List for 2010. Jaron described his experiences in designing virtual avatars for humans, and went deeper from there to discuss the philosophical implications of human-computer interaction. A line from Jaron that still resonates in my mind is to not believe in computers when designing computers as a computer scientist. That is to say, we need to focus on the humans that these computers and computer applications are designed for rather than on those computers which exist to serve. So often do computer scientists fall in love with their creations just as artists do with their art, and forget about the purpose and the meaning of these creations. Jaron emphasizes that great potential lies in humans and the way they present themselves in the virtual world, and from his talk, I see great respect for and belief in humanity.

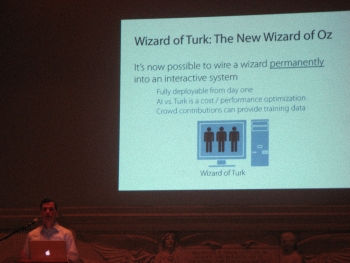

If you’re following UIST 2010, you also shouldn’t miss any paper presented today besides the keynote. The afternoon session includes Bigham’s work on a smart application Mechanical Turk to helping visually impaired individuals (Best Student Paper), Vig’s paper on movie tags with expression elements, Bernstein’s efforts in making Twitter more user-friendly, and the same Bernstein’s work on simplifying your paper writing with Mechanical Turk (Best Paper). The other sessions on Intelligence and Surface are just as inspiring.

I wanted to end today’s post with a quote from Jaron’s keynote, but I found I couldn’t: the talk was in its entirety an amazing piece of work, not only scientifically valuable, but also philosophically profound, and thus no single quote is separable from the context. Therefore, I’m going to end this post by looking forward to next year’s UIST in California, and to what technical advancements can be achieved within a mere year of time.

About the author:

Langxuan "James" Yin is a Ph.D. candidate at the College of Computer and Information Science at Northeastern University. James' research is focused on creating conversational virtual characters tailored to cultural minorities that improve the target population's health and promote their health behaviors. He is also an active webcomic artist.

No entries found