Communications of the ACM

Microscopic Trampoline May Help Create Networks of Quantum Computers

Robert Peterson works with a "dilution refrigerator" which can cool a quantum "trampoline" down to a fraction of a degree above absolute zero.

Credit: Peter Burns

A microscopic trampoline could help engineers to overcome a major hurdle for quantum computers, say researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Their work is described in "Harnessing Electro-Optic Correlations in an Efficient Mechanical Converter," published in Nature Physics.

The research targets an important step for practical quantum computing: How can you convert microwave signals, such as those produced by quantum chips made by Google, Intel, and other tech companies, into light beams that travel down fiberoptic cables? Scientists at JILA, a joint institute of CU Boulder and NIST, think they have the answer: They designed a device that uses a small plate to absorb microwave energy and bounce it into laser light.

The device can jump this gap efficiently, too, says JILA graduate student Peter Burns. He and his colleagues report that their quantum trampoline can convert microwaves into light with close to a 50 percent success rate—a key threshold that experts say quantum computers will need to meet to become everyday tools.

Burns says that his team's research could one day help engineers to link together huge networks of quantum computers.

"Currently, there's no way to convert a quantum signal from an electrical signal to an optical signal," says Burns, one of two lead authors of the new study. "We're anticipating a growth in quantum computing and are trying to create a link that will be usable for these networks."

Quantum Translation

Such networks are on the horizon. Over the last decade, several tech firms have made inroads into designing prototype quantum chips. These devices encode information in what scientists call qubits, a more powerful storage tool than the traditional bits that run a laptop computer. But getting the information out of such chips is a difficult feat, says Konrad Lehnert of JILA, a co-author of the new research.

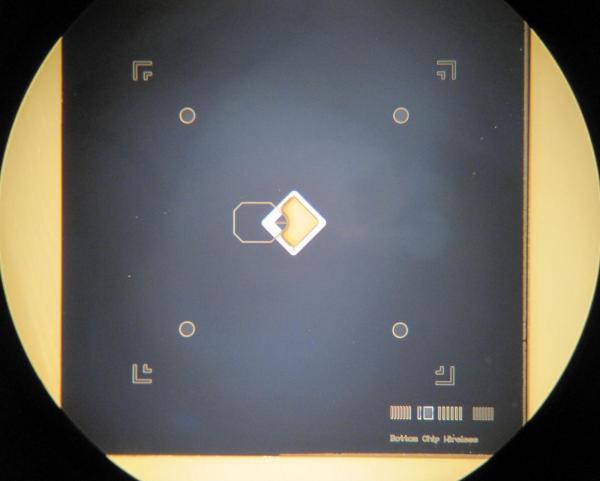

This chip, designed by researchers at JILA and measuring less than a half-inch across, converts microwave energy into laser light.

Because outside interference can easily disrupt quantum signals, "you have to be cautious and gentle with the information you send," says Lehnert, a NIST fellow.

One big challenge lies in translation. Top-of-the-line quantum chips like Google's Bristlecone or Intel's Tangle Lake send out data in the form of photons, or tiny packets of light, that wobble at microwave frequencies. Much of modern communications, however, relies on fiberoptic cables that can only send optical light.

In the newly published research, the JILA group approached that challenge of fitting a square peg into a round hole with a tiny plate made of silicon-nitride. The team reports that zapping such a trampoline with a beam of microwave photons causes it to vibrate and eject photons from its other end—except these photons now quiver at optical frequencies.

The researchers were able to achieve that hop, skip, and a jump at an efficiency of 47 percent, meaning that for every two microwave photons that hit the plate, close to one optical photon came out. That's a much better performance than other methods for converting microwaves into light, such as by using crystals or magnets, Burns says.

He adds that what's really impressive about the device is its quietness. Even in the ultra-cold lab facilities where quantum chips are stored, trace amounts of heat can cause the team's trampoline to shake. That, in turn, sends out excess photons that contaminate the signal. To get rid of the clutter, the researchers invented a new way to measure that noise and subtract it from their light beams. What's left is a remarkably clean signal.

"What we do is measure that noise on the microwave side of the device, and that allows us to distinguish on the optical side between the signal and the noise," Burns says.

Getting Networked

The team will need to bring down the noise even more for the trampoline to become a practical tool. But it has the potential to enable a lot of networking. Even with recent advances in quantum chips, modern devices still have limited processing power. One way to get around that is to link together many smaller chips into a single number-cruncher, Lehnert says.

"It's clear that we are moving toward a future where we will have little prototype quantum computers," Lehnert says. "It will be a huge benefit if we can network them together."

Andrew Higginbotham, now at Microsoft Research, was the co-lead author of this research. Other co-authors included Maxwell Urmey, Robert Peterson, Nir Kampel, Ben Brubaker, Graeme Smith, and Cindy Regal, all at JILA. Additionally, Smith is an assistant professor and Regal is an associate professor in CU Boulder's Department of Physics.

No entries found