Communications of the ACM

Estonia's E-Society: Visionary or Naive?

Electronic voting is just one of the ways in which Estonia has embraced information and communication technologies.

Credit: vilnews.com

When I visited Estonia for four days in mid-May, its citizens were just starting to vote, via computer or smartphone, in the European Parliamentary elections. Kristjan Vassil, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Tartu, the country's national university, showed me and some other journalists how electronic voting works in Estonia: he connected a card reader to his laptop, and signed in with his electronic identity card. He then logged onto the voting site and identified himself with an initial PIN code, cast his vote, and used a second PIN code as an electronic signature ensuring his anonymity.

We asked, wasn't it strange to have a bunch of foreigners watch him vote? "No problem," he said, "this is only a demonstration." The next day, he would log on again and vote for the candidate he really wanted to support; Estonians are allowed to change their minds, and their electronic votes, as often as they please over a seven-day voting period (of course, the final vote registered is the one that will count).

Estonia introduced electronic voting in 2005; May's European election was the sixth in which citizens could choose to vote either on paper or electronically. Back in 2005, only 2% of eligible voters cast their votes electronically; for the 2014 European elections, a record 31% of the electorate voted electronically.

Never before have I seen a country adopt ICT in all domains of life as enthusiastically as Estonia, which not only has implemented e-voting, but also e-tax, e-customs, e-healthcare, e-banking, and e-schools. The country has even launched a nationwide scheme to teach students in public schools, ranging in age from 7 to 19, how to write code.

Estonia is a small country, with just 1.3 million inhabitants living in just over 45,000 square kilometers, an area larger than Maryland but smaller than West Virginia. The entire country is covered by 3G/4G mobile data networks, and there are more than 1,100 Wi-Fi hot spots, most of them free for public use.

The Skype voice-over-IP service was developed in Estonia in 2003; today, it handles 40% of international telephone traffic. Skype has become an example for numerous other Estonian ICT start-up companies, among them the rapidly growing money-transfer company TransferWise.

Why are Estonians such whole-hearted early adopters of ICT when, hearing about all the personal data the Estonian government holds, and with the U.S. National Security Agency spying disclosures in the back of their heads, most citizens of Western countries would quickly envision the all-intrusive 'Big Brother' from Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four? In Estonia, however, most people seem to think just the opposite. They can now see on their computers exactly what information the government has on them and, even more importantly, they can also see if anyone accesses that information; if an unauthorized person opens one of their files, a red flag goes up.

Why Estonia?

Two important factors explain why ICT has increasingly been integrated into the DNA of this entire whole nation.

The first is political. Estonia declared its independence in 1991 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Estonia's first prime minister, Mart Laar, was only 32 years old at that time, and the average age of people in the Estonian government was only 35. This very young government realized computers and Internet could be the perfect counterbalance to a country with few citizens, so the government decided to invest heavily in ICT. By 1996, most schools were equipped with computers, and by 2000 most Estonians could file their income taxes electronically.

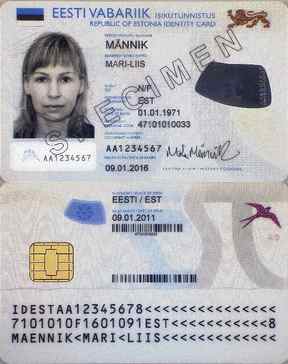

The second reason behind Estonia's enthusiasm for ICT is the success of the electronic identity card, the e-ID. Introduced in 2002, the card initially allowed citizens to access to all information the government had collected about them. "The government needs to work as efficiently as possible," says Anna Piperal, marketing project manager of the ICT Demo Centre in the Estonian capital Tallinn, "and for this to happen, the digitization of communication between citizens and government is crucial. The e-ID has been a success because the card has gotten so many different applications."

Almost every year since its introduction, a new application has been added to the e-ID: public transport payments, banking access, access to electronic voting, access to electronic health records, library access, and even driving license records. Also, thanks to an electronic education system, parents, teachers, and students can use the cards to access a database of students’ test results and homework assignments at any time. The e-ID has truly become an all-in-one-card.

"Other countries can create an e-society as well," says Piperal. "All they need is the political will and the ability to make the needed adjustments to their legal system." In addition, I would add, they will need great trust in their government, as well as in the security of ICT solutions and the ability to keep data private.

For some this seems to come naturally. Security specialist Anton Veldre says he lived half his life under the Soviet regime, when Estonia was part of the Soviet Union. "Paper elections back then, with the only choice being for or against the Communist Party, were a big joke. They were completely manipulated. That’s why we don't trust voting on paper."

General facts about Estonia

Population: 1.3 million

Area: 45.226 km2

Independent since 1991

Joined the European Union: 2004

Using the euro as currency since 2011

Timeline of Estonia’s e-Society

- 1996: Introduction of computers to all schools

- 2000: e-Tax system introduced; m-Parking introduced (permits paying for parking via mobile phone).

- 2002: e-ID Card rolled out to allow all citizens to enable access all government information, and also for electronic banking.

- 2002: X-Road introduced as backbone of Estonian e-infrastructure: provides a distributed, secure, unified web-services-based inter-organizational data exchange framework.

- 2003: e-ID Card authorized for use as payment for public transportation.

- 2005: e-Voting enabled.

- 2007: e-Police enabled (all patrol cars are equipped with mobile workstations and positioning systems that track the location and status of each vehicle)

- 2007: Mobile ID enabled; X-Road survivs a nationwide cyberattack.

- 2008: e-Health applications enabled.

- 2010: e-Prescriptions added to e-Health capabilities.

- 2013: The X-Road infrastructure is made available to other European nations. Finland has signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Estonia to roll out X Road; other Scandinavian countries are considering it as well.

- 2013: Online Border-Crossing Queue System introduced.

- 2014: Estonians vote electronically (via computer or smartphone) for European Parliament

Future plans for Estonia’s e-Society

- 100 Mbps Internet connectivity for every home by 2017.

- All retailers to have the capability to provide e-receipts.

- Virtual residency: making it possible for foreigners not living in Estonia to open businesses within its borders the same way Estonians do, and to obtain e-IDs without being Estonian residents.

- Data Embassies: Back-ups of data of the Estonia e-Society not only in Estonia, but also through Estonian embassies all over the world.

- Cross-border e-Services: Enabling anyone to set up a company in Estonia from abroad.

Internet Gateway to eEstonia: www.eesti.ee

Bennie Mols is a science and technology writer based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

No entries found