Communications of the ACM

San Francisco: An Iot City

An Internet of Things prototype being worked on at a hackathon in San Francisco to spur development of devices compatible with the Sigfox network.

Credit: Sigfox

Late in October, the City of San Francisco flipped the switch on a new network designed to support the Internet of Things (IoT).

The one-year pilot project is the result of the city’s partnership with the French company Sigfox. Based near Toulouse, France, Sigfox has been actively installing its networks throughout Europe and expects to have them in cities in 60 countries within the next five years.

San Francisco is the company's first installation in the U.S. and, according to executive vice president for communications Thomas Nicholls, Sigfox could not have made a better choice. The first meeting with city officials was two years ago, and "when we explained what it is we're doing, their initial reaction was 'how can we get that network to the great startups in San Francisco?'" recalls Nicholls. "They suggested that we collaborate on getting access to sites for installing the network, and also with helping get people up and running. We had never had that sort of suggestion from any other city in the world."

"I don't know if they called us or we called them," says Miguel A. Gamiño Jr., San Francisco’s chief information officer and executive director of the city's Department of Technology. "We were thinking about and exploring the concept of IoT, but we weren't thinking 'we need to go find someone who's got a low-bandwidth WAN solution.' We didn't know what we didn't know. But from the very beginning, we were interested in developing a partnership and seeing it evolve to the point we're at today, where we've launched the network."

Even with an enthusiastic city, the establishment of the network did not happen right away. At the time of the initial conversations, Sigfox was not yet ready to operate in the U.S. "It doesn't make sense for us to just get the network up and running," says Nicholls. "We need tools and resources to help bring solutions to the network. Once we got to the point where we could provide those resources, we got back to the city and said 'we're ready now.'"

The company's U.S. headquarters are in Boston, and it also has a location in San Francisco.

Nature of the network

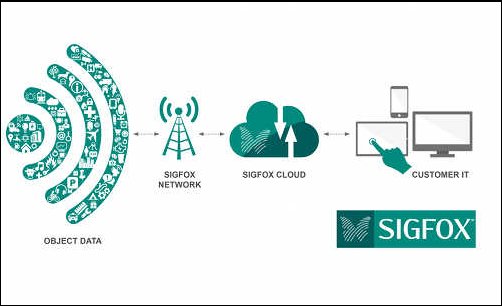

Sigfox's approach, according to Nicholls, is based on the idea that if you can compromise on the number and size of messages a device sends, you can lower the cost of both the network and the devices, as well as lowering their energy consumption. "A device that uses the Sigfox network is not 'connected' to the network," says Nicholls. "You could have a device on a water pipe that has a humidity sensor; as soon as it detects humidity, it wakes up, sends a message to say 'hey, there's a leak,' and then it goes back to sleep."

The fact that it deals with such small, one-off messages lets the company use ultra-narrow band radio technology to connect devices. That enables the network to handle a large number of messages in a small frequency range while requiring little energy consumption. The Sigfox network operates in the unlicensed industrial, scientific, and medical (ISM) wireless frequency band of 902 MHz in the U.S. and 868 MHz in Europe, which opens the network to off-the-shelf radio components, says Nicholls. "You can basically take any sub-giga chip from Texas Instruments or Silicon Labs, and that chip will work with Sigfox." A solution provider would then need to purchase a data subscription to gain access to the network.

Existing wireless vendors, from carriers such as AT&T and Verizon to Wi-Fi vendors like Cisco, also are developing networks to support the IoT and smart cities. Nicholls is quick to point out that Sigfox is complementary to other connectivity solutions: "we're focusing on enabling new use cases that didn't exist before," he says. "We're in no way out to compete with them--and the thing is, we couldn't." For example, Sigfox couldn't support large messages such as multimedia, nor do its devices need to be in constant communication.

On a cellular network, each device is communicating with one cell, and where there are lots of people in one area, a provider must have lots of cells to handle the traffic. Furthermore, a mobile phone constantly checks with the network to make sure it still has a connection and to negotiate the handoff from as it moves from one cell to another. "With us," explains Nicholls, "the 'things' don't know about the network. You don't have a device connected to one node. When a device sends a message, it's picked up by all of the cells that are in sufficient proximity." Sigfox deduplicates messages in the cloud so the customer receives only one copy.

From where Gamiño sits, Sigfox does not seem to be stepping on any other vendor's toes. "I'm in pretty frequent contact with all the big players, and I have not received any pushback from them at all," he says. "If the existing big carriers want to carve out some of their unlicensed spectrum for IoT-specific use cases or development, I'd welcome that. We're building an ecosystem, we're not building any kind of exclusive situation for Sigfox or anybody else."

City side

When asked how the city plans to make use of the Sigfox network, Gamiño says it is too early too tell, but the development of an IoT-oriented ecosystem fits the city's identity as a hotbed of technological innovation. "I don't have a prescriptive list of the things we intend to develop," Gamiño says, "but one of our core industries is technology, and it's also important for us to maintain an environment that is vibrant and ripe for invention. The next wave of startups that develop around the IoT solutions--I'd really like to see those companies develop here."

Gamiño also looks forward to what he calls "civic-service use cases." Some such solutions will be internally developed, while others will rely on third parties or on public-private partnerships. "I think it's a matter of presenting problems and seeing what sort of creative solutions come from an open and engaged process," says Gamiño.

As a first step in encouraging such projects, Sigfox and San Francisco's Department of Technology in November sponsored a two-day hackathon in which contestants developed prototypes for devices that could use the network. The 150 participants were asked to come up with devices that would make San Francisco a "smarter city" when addressing issues like air quality, water usage, and transportation. The winning projects included:

- Audio Argus, which uses acoustic waves to monitor the condition of mechanical devices ranging from vehicles to air conditioners, to determine if they need maintenance before they break down.

- WaterSaver, which relies on live metrics, forecasts, and machine learning to turn on garden sprinklers when needed.

- DryWater, which also uses moisture sensors and machine learning to control garden watering schedules.

- Better Bike, which uses GPS tracking and distance sensing to make commuting by bicycle safer.

At this early stage, Gamiño emphasizes, there is no telling what IoT solutions ultimately will look like. "There are some obvious use cases," he says, "but I think people will come at the problems from a completely different perspective now that connectivity is a given. It's like people in the '80s trying to say, ‘what is the be-all end-all for the Internet?' Nobody back then would have predicted Airbnb."

Jake Widman is a San Francisco, CA-based freelance writer.

No entries found