Communications of the ACM

Hand Printing

Networks of three-dimensional printer owners create low-cost hands and limbs to help those in need.

Credit: Limbitless Solutions

Relatively affordable consumer three-dimensional (3D) printers have taken the world by storm over the past few years. According to technology analyst Canalys, shipments of 3D printers selling for less than $2,000 rose from 13,800 in 2013 to 25,800 in 2014 to around 60,000 in 2015, for purposes ranging from rapid prototyping of products to designing home décor items to building guns.

That rapid growth has spurred interest in another application as well: supplying functional hands and arms for those who were born without them or lost them in accidents or war. The low cost of the printers and raw materials make these prosthetic devices more affordable and widely available than professional, medical-grade models.

One of the leading organizations involved in this movement is e-NABLE, a group of "7,000 volunteers, if not more" in 45 countries, according to Aaron Brown, who runs a retail print shop in Grand Rapids, MI, and has worked with e-NABLE since nearly its beginning two years ago. People who own a 3D printer or have access to one can download tutorials, materials advice, and other resources from the e-NABLE website. In addition, Brown says, "there’s a matching system where a family could email us, and we’ll try to find an e-NABLE volunteer in their community. If no one’s available, we’ll find somebody to print and mail them the parts. We’re able to take all the sizing and measurements through photographs and email."

Brown says the fact that e-NABLE gives its devices away is an important aspect of how the group operates. "Legally, if you sell prosthetics, you have to be a certified and licensed prosthetist or occupational therapist," he says, explaining that e-NABLE prefers to call its products "assistive devices" rather than "prostheses." "We don’t want to take anything away from the medical-grade devices and the talented, hard-working prosthetists who are making devices that are many times stronger than the ones we’re doing."

If you build it

Part of what makes e-NABLE’s devices so accessible is that its designs are open source and its tools are inexpensive. "The beauty of 3D printing is that you can design something and print it out for very cheap—a hand uses just $10 worth of plastic," Brown says. "So if you want to test a new design, you just draw it up, print it, and test it. If it works, great; if you need to change something, you just jump on the computer and start doing some iterations." Once a design is tested and approved, e-NABLE puts its design online for anybody to download and use, or tweak to their own requirements. So far, the organization has posted about a dozen working designs.

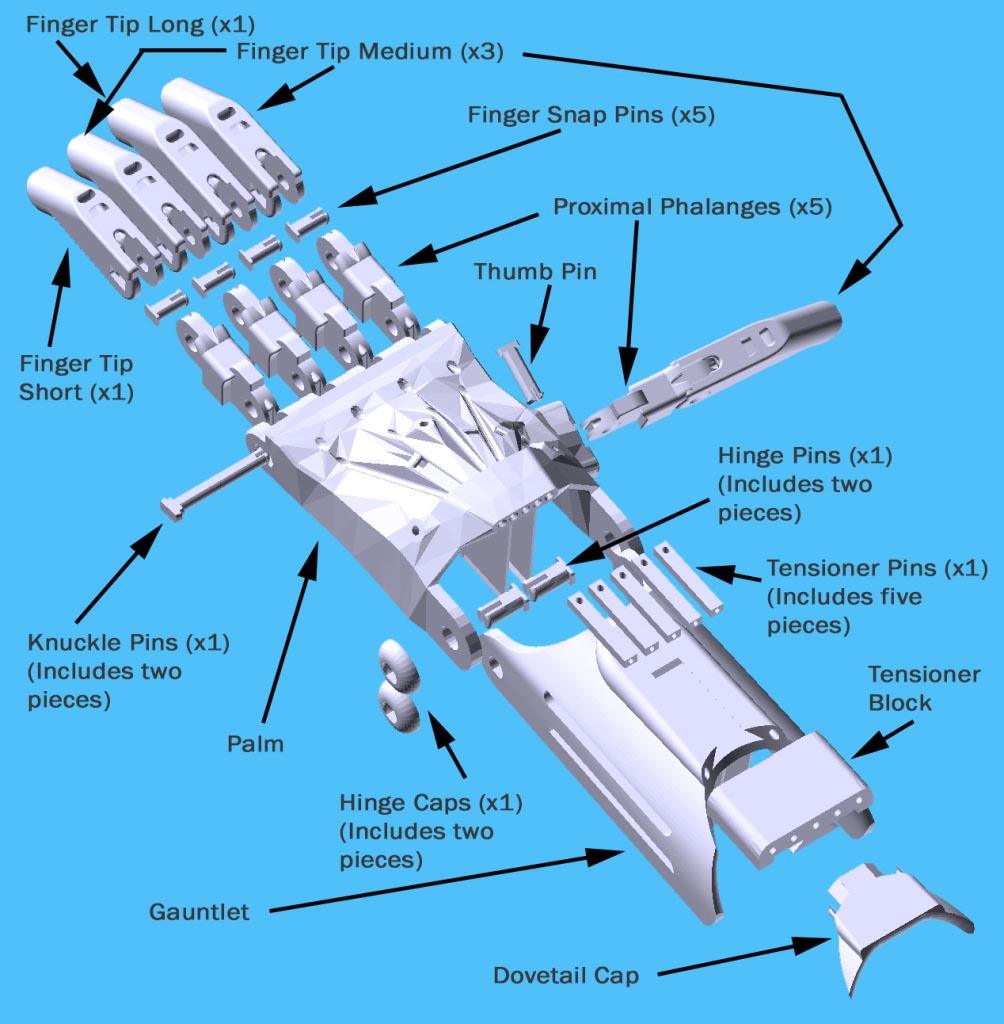

Users can download files for printing the pieces of a prosthetic hand

as well as assembly instructions from the e-NABLE website.

Credit: e-NABLE

The organization’s software is freely accessible, too. "A lot of members, including myself, use free CAD software, such as Tinkercad, 123D Design, or Onshape," says Brown. The software is used to create a STereoLithography (STL) file, the format the designs are uploaded in and which, for the most part, other software can open and edit.

For printing, the STL file is sent to "slicing" software that divides the 3D model into layers the printer will lay down one by one. The slicing software sends the printer a stream of all-text g-code. "That’s what tells the printer, ‘heat your nozzle up to this temperature, move it over to here, draw a line from here to here,’" explains Brown.

All can play

Other organizations around the world are engaged in similar efforts. Open Bionics, based in the Bristol Robotics Lab of the University of the West of England, in February announced the release of its first open source 3D robotic hand kit. The company has also been working with Lucasfilm, Marvel, and Disney to design devices with artwork based on the movies Star Wars, Iron Man, and Frozen, respectively.

In Japan, Exiii is working on designs for the Hackberry 3D-printed bionic hand, which it intends to release open source as a platform for people to customize as they wish.

Others have chosen to build the arms themselves. Limbitless Solutions, based at the University of Central Florida, "started as a summer project in 2014 with myself and some friends with engineering and computer science backgrounds," recalls founder Albert Manero. That project, to create an arm extending above the elbow, was carried out in conjunction with e-NABLE.

The arm was made of 3D-printed plastic parts, but it also included electronics. According to Manero, "The biggest distinction between the devices designed by e-NABLE and those made by Limbitless is that the former are purely body-powered, while the latter are controlled by electronics that read the electrical signals from the wearer’s muscles. We’ve been able to complement each other quite nicely."

The electronics add to the cost of the devices, however; Manero estimates that first arm cost about $350, which came out of his pocket. For that reason, his group formed a nonprofit organization to help raise funds for its more expensive limbs. It has also brought production in-house to have greater control over quality, and to be able to continue evolving the designs.

Limbitless relies on more flexible 3D design tools as well, such as Blender or Maya, because of its devices’ complex shapes.

Unmet needs

The low cost of these 3D printed hands and arms make them particularly suitable for the under-served children’s market. "It’s rare for a child to get a medical-grade device," says Brown, "because they grow so fast, and a lot of time insurance companies won’t cover it, or families can’t afford the co-pay every 12 months. So we’re filling this need for smaller devices."

Because the devices can be shipped as separate parts and assembled on site, e-NABLE has also been able to supply its devices in bulk. One such shipment has gone to a children’s hospital, while another was sent to Syrian refugees.

Paying it forward, e-NABLE is also making an effort to get children involved on the creation side. "We’re trying to do a massive movement into schools, libraries, maker spaces, and the like, getting kids involved with some of the software," says Brown. "They think they’re having fun—some of it is almost like Minecraft. They’re mostly designing toys, Christmas ornaments, and Mother’s Day presents. But I always joke that one of these days, one of these kids will 3D print us a new heart."

Jake Widman is a San Francisco, CA-based freelance writer focusing on connected devices and other smart home and smart city technologies.

No entries found