Communications of the ACM

Consumers and 3D Printing: The Future

Consumer adoption of three-dimensional printing has not yet taken off in a substantive way, but that could be changing.

Credit: tested.com

Consumer adoption of, and excitement about, three-dimensional (3D) printing has not yet taken off in a substantive way. That could be changing, however, as 3D printer manufacturers spoon-feed information to consumers on the technology’s potential while delivering on what they actually want: easy customization at an affordable price.

One indication of the growing significance of consumer 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing and rapid prototyping, came in April at the 6th White House Science Fair, when a nine-year-old maker, discussing his experiments with 3D printing, suggested President Obama appoint a "kid science advisor." (The president was receptive to the notion, and suggested bringing together a group of youngsters to share what they think is important in science, technology, and innovation.)

Nevertheless, the consumer 3D printer market "looks some way off," according to SmarTech Markets Publishing’s April 2016 report, while that organization "is seeing the rapid development of a professional market for 3D printers—at architects and designers, for example." Disappointments such as Stratasys’ failed venture to manufacture 3D printers for the consumer market illustrate the consumer market still has a way to go.

Bill Decker, chairman of the Association of 3D Printing, agrees the consumer market for 3D printers is largely untapped, although he noted, "Best Buy, Barnes & Noble, the big box retailers are betting on it." What is helping to "escalate the market are small, handheld 3D printers sold by Brookstone, such as the 3Doodler, which is like an electric toothbrush, an advanced glue gun." Such products, Decker said, are inexpensive, and because they do not require software like their desktop brethren, are super-easy to use.

Building a three-dimensional model

with the 3Doodler.

Credit: the3doodler.com

Decker adds, "It’s a disruptive technology, and you’re seeing more and more of it in education, on the Internet, and with e-publishing. And when the kids see it and use it in school, they want to have it at home."

Maxim Lobovsky, CEO of 3D printing product developer Formlabs, which started at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Bits and Atoms, agreed education will help spur the consumer 3D printing market, as did Nadya Peek, research assistant at the Center for Bits and Atoms. Peek said 3D printing is "a great educational tool where the parent works with a child on 3D modeling and tool pathing and then printing." However, she noted, there is an "expectation that the consumer needs to learn AutoCAD or Pro/E or any of the industry specific tools, although if the tools to make 3D design are easy, they can start prototyping right away."

Braydon Moreno, co-founder of 3D printer manufacturer ROBO 3D, which has a presence in big-box retail stores, takes the long view, but thinks consumer acceptance needs to be nudged along. "We need to spoon-feed things that consumers can make with the product, so it’s shifting the focus from being not just on hardware, but on developing the content; not just content you find online, files you find that you can actually print, but physical things we can sell that they can take home and print."

His company sells 3D Printer Packs that include a "thumb drive that comes in a little package that has 20 theme files that we’ve created for household items, things for the garden, for the kitchen, the office. And the consumer can see, 'these are things I can easily design and customize to improve my life.'"

ROBO 3D goes one step further by supplementing printer designs with hardware; for example, its drone print kit includes not just instructions for building a drone quadcopter and customizing its body style, but also a motor and controller, components which cannot be printed. Moreno emphasized the importance of developing more ideas "to fuel consumer understanding, and then they will become more creative and download free files to do their own."

However, says Decker, the emerging consumer 3D printing market with the greatest potential, "which is life-changing, is for people with disabilities, because everyone is unique. For example, someone with Parkinson’s (disease) can’t hold their own toothbrush, so you can 3D-print a bracelet to hold that toothbrush in place, or a straw in a drink to help with the shaking." People can "make their own custom models that fit their hands perfectly," he said.

Decker noted two trends that could hasten the consumer market. First, the many available file-sharing services make it easy for consumers to find designs they can print, with the understanding they will not pirate those designs (which Decker described as "faith-based currency"). Second, 3D scanning is becoming increasingly affordable, Decker said, and will become so user-friendly that "ultimately, it will come down to the camera in an iPhone, so no separate scanner will be needed."

On the other hand, while he agrees 3D printing is currently dominated by hobbyists and professional makers, Lobovsky doubted consumer adoption would take off any time soon. He sees the market for consumer 3D printing developing much like that of the desktop computer, which was introduced in the early 1980s and "which really didn’t take off until the late ‘80s and early ‘90s." Today, he said, "There are desktop 3D printers for the hobbyist market, but it’s not on track to the mass market."

Said Lobovsky, "At present, the value is in using 3D, printers and not what they produce for you. Ultimately, if this is beyond a hobbyist use case, then the value has to be in what it does for you, not the act of using it, which is what defines the hobbyist market."

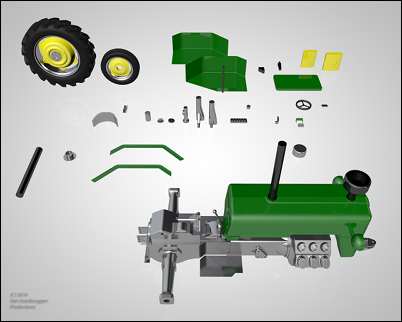

Both Decker and Moreno said 3D printing is great for creating replacement parts "in areas where you can’t get stuff quickly," Decker said, such as if you are on a remote "farm in Nebraska and you quickly need an O-ring to fit your tractor."

Three-dimensionally printed tractor parts.

Credit: Van Osenbruggen Productions

Also, those replacement parts can be customized; for example, Moreno says, "Imagine printing out a replacement showerhead that is a T-Rex, which will get kids to shower."

Considering the cost of materials, Moreno said 3D printing can make economic sense; "A smartphone case costs from $19 to $100, but you can print it for 10 cents."

Looking to the future, Decker says 3D printers will be able to utilize green materials, such as grass and water, or recycled bottles. Moreno says ROBO 3D has starting to use new materials, such as "wood-infused plastics that print out to look and smell like wood and can be sanded and painted or scent-infused, which makes it fun."

When the consumer 3D printing market does start to take off, Decker said he expects that to bee accompanied by "opportunities for rip-offs and counterfeiting" of 3D designs. Of course, there will also be safety and liability issues; for example, "it’s easy to scan a head to print bike helmets, but what happens if there is an accident and the helmet offers no protection?"

Clearly, as Moreno said, "certification and authentication" of 3D designs will be the next step "to sell in the open marketplace, but it won’t be expensive because there will be no overhead and inventory. It’ll be the new age of ecommerce."

There also is the matter of making it easy to 3D-print at the right price point. Moreno said ROBO 3D had fielded surveys and found the $500-$1,000 range was the "sweet spot" for these printers; less than $500, and consumers considered them to be "cheap."

Consumer adoption of 3D printers is less a question of "if" than of "when." As Moreno said, 3D printing "gives you the opportunity to make things you would never find, to customize and personalize them. So companies would provide designs and you could print them out. Once there are enough practical and cool things that are accessible (to scan with smartphones), people will enjoy the creative and practical elements."

Tatjana Meerman is a freelance technology writer based in the Washington D.C. area.

No entries found