Communications of the ACM

Fear of Job Loss to Automation Hurts Productivity

Workers' growing fears of having their jobs being replaced by automation have a direct impact on both worker health and productivity.

Credit: Techcrunch.com

We stand at the precipice of the fourth Industrial Revolution. The first Industrial Revolution saw the advent of steam-powered mechanization), the second the utilization of electricity to run production machines, and the third the use of computers to control production automation. The fourth Industrial Revolution is being spurred by combining artificial intelligence (AI) with robotic devices.

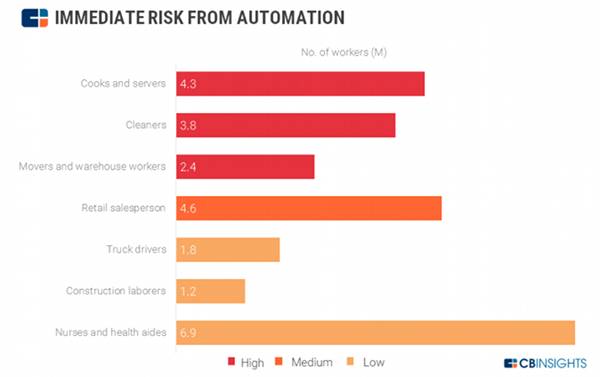

Unfortunately, this latest evolution threatens almost 24 million U.S. workers—both blue and white collar—with unemployment, according to New York City-based market research firm CB Insights, which cites the jobs of cooks, servers, cleaners, movers, warehouse workers, retail workers, truck drivers, construction laborers, nurses, and health aides as being at greatest risk of elimination due to automation.

Compared to the Great Recession of 2007-2009, which eliminated 8.7 million jobs, according to CB Insights, current trends in automation threaten even more, including 10 million service and warehouse jobs over the next 5 years, nearly five million retail workers over the next 10 years, plus another nine million service workers in the long term, including drivers, construction laborers, and medical workers.

To make matters worse, the fear of job loss due to automation, combined with confusion over which skill sets need to be acquired to be employable in the future, is already affecting worker health and productivity. Social scientists have determined the degree of perceived certainty that one's job will be automated out of existence is directly correlated with increasing physical and mental distress among today's workers.

A recent nationwide study found that every perceived 10-percentage-point increase in the fear of being replaced by automation correlates to a 2.38-percentage-point decline in the health of workers. The effect of this drop in health and its resulting presenteeism (working while sick, the opposite of absenteeism), according to the study, already amount to an overall $24-million to $174-million annual loss in U.S. productivity, in addition to $6 million to $40 million in medical costs associated with increased physical distress, and $7 million to $47 million in medical costs related to increased mental distress.

Worst of all, this is just the beginning, as the health status of at-risk workers is declining and their associated presenteeism costs are growing daily, according to the study's principle author, Srikant Devaraj of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University in Muncie, IN.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the federal agency charged with ensuring safe, healthy working conditions, is collaborating with the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, an agency of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and the non-governmental Robotics Industry Association (RIA) "to look ahead at the impact robotics will have in workplaces," said OSHA's Kimberly Darby. "When integrating robotics and automation into workplaces, the agency is focused on how workers can work safely with robotics, as well as how robots can make workplaces safer. For example, we are looking at effective risk assessments, hazard recognition, and implementing proper controls."

Unfortunately, the risk of being replaced by automation is already estimated to be as high as 47%, according to a University of Oxford study cited by Michael Hicks, George and Frances Ball Distinguished Professor of Economics and Business Research and professor of economics at Ball State University.

Emily Wornell at Ball State worked with Pankaj Patel at Villanova University, as well as Devaraj and Hicks, on a just-released study on the risk of U.S. job losses to automation, in which the researchers gathered detailed metrics on the impact of job automation insecurity on workers' physical and mental health. "Ours is the first study (to our knowledge) that links the risk of job loss to automation with health status. And the mechanism of impact we hypothesize—job insecurity—is also supported by a recent survey conducted by MindEdge," said Devaraj. Although the MindEdge study offers hard data on the percentage of each job type at risk in the short term, it offers only vague insight into what future skill sets will be needed to be employable in the post-automation future. Likewise, Devaraj's study measures the current impact on workers of their fear of loosing their job to automation, but offers few solutions.

"The objective of our study was to test if occupation-related risk of job loss to automation has a potential impact on regional health. We estimated them from a economic/sociological perspective and believe this method will be an area of interest to other researchers from different fields," said Devaraj.

Devaraj and his colleagues claim to have statistically proven their hypothesis, that job insecurity leads to health risk, by assessing whether workers in occupations exposed to higher risk of job loss to automation reported higher job insecurity which, in turn, was associated with negative health outcomes. The U.S. study found that the Southern region had the highest percentage of people literally worried sick about losing their jobs to automation, compared to people in the Plains, Midwest, and New England.

"We found that the correlation between poorer health and the risk of job loss to automation was statistically significant. Past research has shown that actual job loss due to things like automation and offshoring jobs has long-term mental and physical health impacts and increases mortality for as long as 20 years after layoff. What we were able to show in our study is that it's not just actual job loss, but also the fear or expectation of it, that also has negative health impacts," said Wornell.

A related finding was that "exposure to automation" in a workplace may also induce job insecurity in the workers remaining after a layoff, which then negatively influenced their health and thus presenteeism, called a "mediation effect" in the study. The risk of job loss to automation also was found to induce fear of reduced wages, which in turn exacerbated family stress and promoted social withdrawal. Further, the authors suggest threats from automation—both actual and perceived—may not immediately affect negative outcomes, but nevertheless gradually increases the prevalence of poorer health eventually deteriorating into physical and mental health issues that often have a direct and lasting impact on the individuals, their families, and communities.

What can be done? Besides future-proofing jobs by teaching workers new, as-yet-undetermined skills, the researchers say they also need to pinpoint immediate interventions to mitigate the negative influence of workers' perceived risk of job loss to automation on their health and productivity.

"We're working on a couple of projects already. The one I'm most closely involved with is looking at the gender and race dimension of automation and offshoring jobs," said Wornell. "Mitigation is something that both researchers and policymakers are pondering. Increasing workers' transferrable skills may lessen the stresses of losing a job and of being afraid of losing a job. Also, better access to health care, including mental health care, particularly for workers who don't have good employer insurance, but whose jobs are at high risk of automation, would certainly help too."

R. Colin Johnson is a Kyoto Prize Fellow who has worked as a technology journalist for two decades.

No entries found